It was a cold, foggy winter morning in December 1860 when the young master locksmith Christian Moritz Westphal made his way from Wandsbek to Reinbek to report the opening of his locksmith’s workshop to the Holstein-Danish administration. At that time, Wandsbek was still a small town in the Duchy of Holstein, and Hamburg was barely an hour’s drive away. Politically, however, it was a different world. Anyone who set up a trade in Wandsbek did not need permission from the Hamburg Senate, but rather the approval of the responsible district administration under the Intendant’s office in Reinbek.

It was a busy time. Between the remnants of the old guild system and the emerging industrial society, craftsmen and small entrepreneurs sought their place in Wandsbek. The town had long since shed its village status and had become a factory town with extended trade rights. By the mid-1850s, Wandsbek already had a good 5,000 inhabitants. Mills, breweries, textile and other businesses were located here. Many workshops and stores were located on the first floor, with families living above in often cramped, simple apartments.

Work was long and hard, usually well beyond a ten-hour day, without social security. At the same time, better roads, steamships and the approaching railroad opened up new sales opportunities in the fast-growing trading city of Hamburg, whose port was developing from a regional transshipment point into the hub of the first globalization.

Politically, the great upheavals of the revolution and the Schleswig-Holstein uprising were less than ten years in the past, and the country was still under Danish sovereignty. However, everyday life was now dominated by a phase of relative calm, in which national tensions smouldered in the background while people tried to make a living. However, the insecure situation with low wages, insecure employment and growing contrasts between the haves and have-nots was palpable. In this transitional period, confinement and scarcity mingled with the quiet spirit of optimism of a generation that sensed that new machines, new transportation routes and new markets also held opportunities for a young master locksmith just outside Hamburg, if he was prepared to take the risk of running his own business.

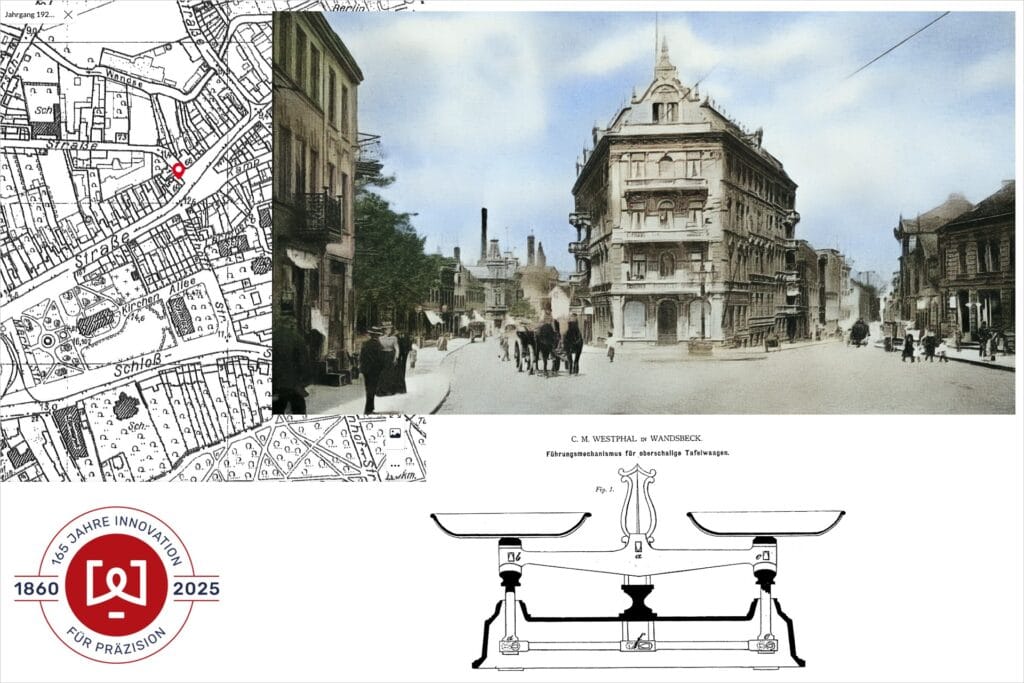

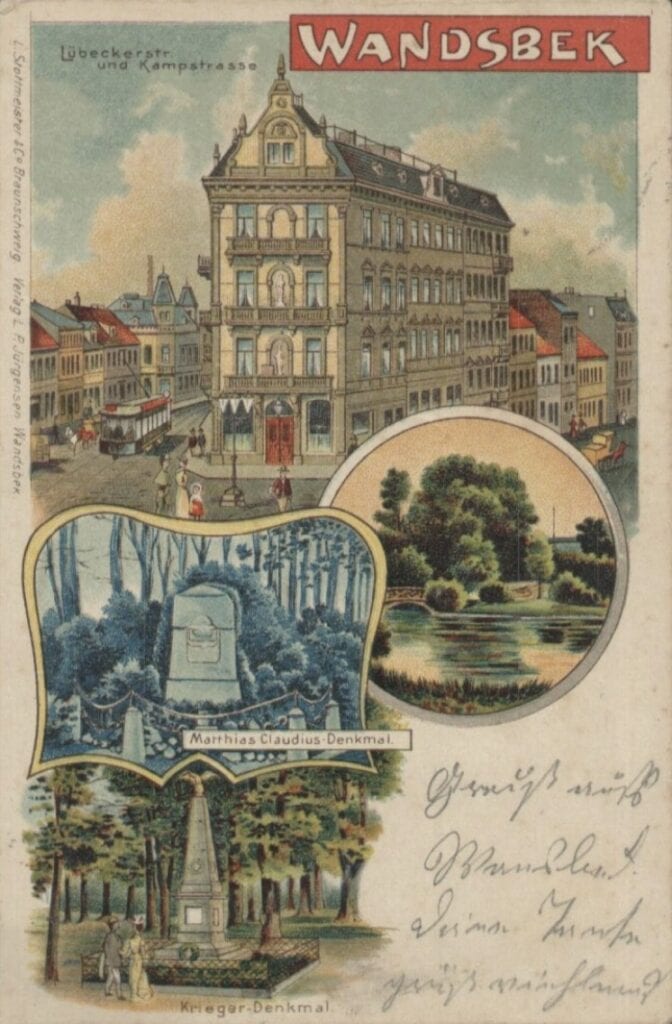

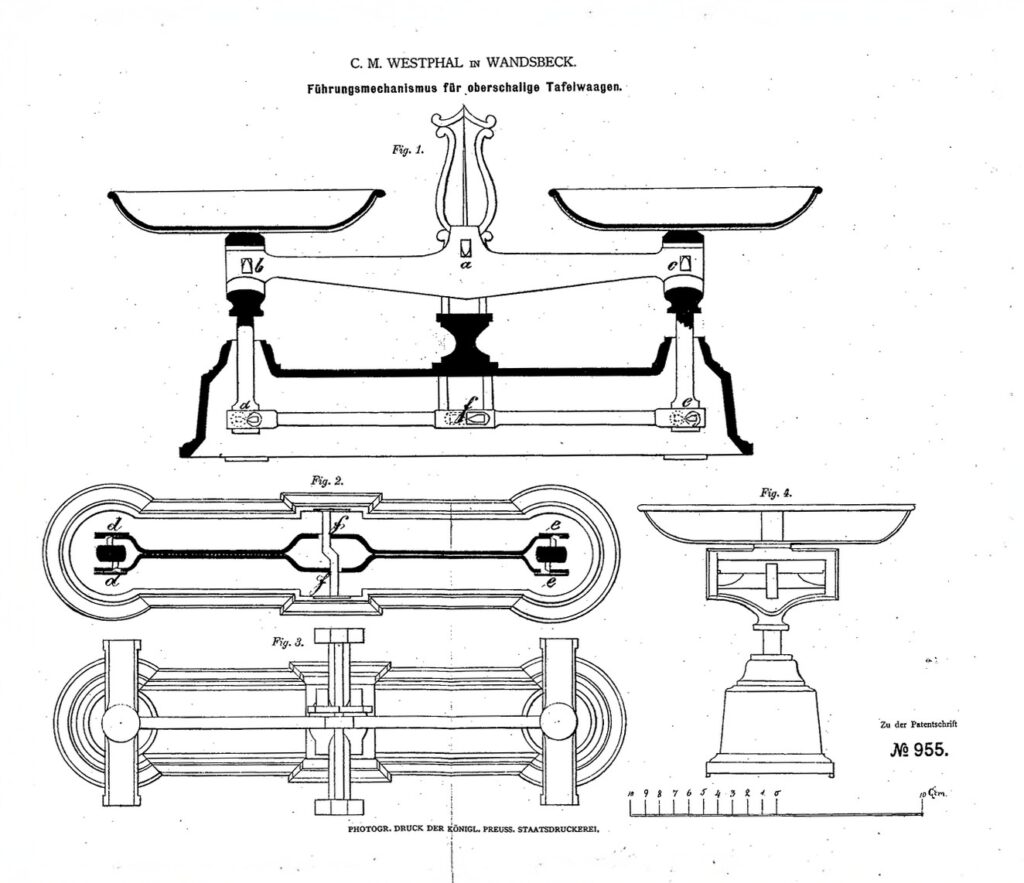

And so the locksmith Westphal settled in Wandsbek near the market square, at what was then Lübecker Straße 62, on the corner of Kampstraße (today’s Wandsbeker Marktstraße). He made a name for himself, specializing in scales from 1873 and taking on his two nephews as apprentices. Westphal developed a guide mechanism to improve the weighing accuracy of top pan scales by moving the pan holders symmetrically. And he registered this as a patent on July 2, 1877 under the number 955 at the the Imperial Patent Office founded the day before. founded the day before.

Christian Moritz Westphal laid the foundations for a success story in Hanseatic scale manufacturing. When he died childless in 1878, his two nephews Albert and Ludwig Essmann took over his workshop. They were not even 18 years old at the time. In the decades that followed, they developed the small, well-running scales business into one of the most important scales companies with trading partners worldwide, building the Ottensen scales factory and registering at least 60 patents.

His legacy remained in the Essmann family for five generations. In 2021, a new management team took over, one that continues to think consistently about scale construction and is committed to the same